Music & Soundbyte 00:00

Puerco: Stop trying to blend or to mimic what you think the industry or your community wants from you. Represent – always show up who you are, where you came from – that is super valuable and that’s why people will always want to have you as part of their program.

Sally Cooper (00:20)

Hello, hello, and welcome back to What’s in the SOSS, an OpenSSF podcast. I’m Sally and I’ll be your host today. And we have a very, very special episode with two amazing guests and they are returning guests, which is my favorite, Stacey and Puerco. Welcome back by popular demand. Thank you for joining us for a second time on the podcast.

And since we last talked, you both delivered one of the most talked about keynote at KubeCon. Wow. So today’s episode, we’re going to talk to you about CFPs. And this is really an episode for anyone who has ever hesitated to submit a CFP, wondered how to get their talk reviewed through the CFP process. Asked themselves, am I ready to speak? Or dreamed about what it might take to keynote a major event.

We’re gonna focus on practical advice, what works, what doesn’t, and how to show up confidently. And I’m just so excited to talk to you both. So for anyone who’s listening for the first time, Stacey, Puerco, can you tell us a little bit about yourselves? and about the keynote. Stacey

Stacey (01:48)

Hey everyone, I’m Stacey Potter. I am the Community Manager here at OpenSSF. And my job, I mean, in a nutshell is basically to make security less scary and more accessible for everyone at open source, right? I’ve spent the last six or seven years in open source community building across mainly CNCF projects, Flux, Flagr, OpenFeature, Captain to name a few.

And now focusing on open source security here at OpenSSF. Basically helping people connect, learn, and just do cool things together. And yeah, and I delivered a keynote at KubeCon North America that was honestly, it’s still surreal to talk about. It was called Supply Chain Reaction, a cautionary tale in case security, and it was theatrical. It was…slightly ridiculous. And it was basically a story of a DevOps engineer who I played the DevOps engineer, even though I’m not a DevOps engineer, frantically troubleshooting a compromised deployment. And Puerto literally kaboomed onto the stage as a Luchador superhero to save the day. had him in costume and we had drama.

And then we taught people a little bit about supply chain security through like B-movie antics and theatrics. But it turns out people really responded to making security fun and approachable instead of terrifying.

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (03:23)

Yeah. Well, hi, and thanks everybody for listening. My name is Adolfo García-Veytia. I am a software engineer working out of Mexico City. I’ve been working on open source security for, I don’t know, the past eight years or so, mainly on Kubernetes, and I maintain a couple of the technical initiatives here in the OpenSSF.

I am now part of the Governing Board as starting of this year, which is a great honor to have been voted into that position. But my real passion is really helping build tools that secure open source while being unobtrusive to developers and also raising awareness in the open source community about why security is important.

Because sometimes you will see that especially executives, CISOs, and they are compelled by legal frameworks or other requirements to make their products or projects secure. And in open source, we’re always so resource constrained that security tends to be not the first thing on people’s minds. But the good news is that here in the OpenSSF and other groups, we’re working to make that easy and transparent for the real person as much as possible.

Sally Cooper (04:57)

Wow, thank you both so much. Okay, so getting back to call for proposals, CFPs. From my perspective, they can seem really intimidating, but they’re also one of the most important ways for new voices to enter community. So I just have a couple questions. Basically, like, why are they important? So not just about like going to a conference, but why is it important to get

Why would a CFP be important to an open source community and not just a conference? Stacy, maybe you could kick that off.

Stacey (05:32)

Sure, I think this is a really important question. I think CFPs aren’t just about filling conference slots. They’re really about who gets to shape the narrative in our communities and within these conferences. So when we hear the same voices over and over and they show up repeatedly, right, you get the same perspectives, the same solutions, the same energy, which, you know, is also great. You know, we love our regular speakers, they’re brilliant, but

communities always need new and fresh perspectives, right? We need the people who just solved a weird edge case that nobody’s talking about. We need like a maintainer from a smaller project who has insights that maybe big projects haven’t considered, or, you know, we need people from different backgrounds, different use cases and different parts of the world as well. CFPs are honestly one of the most democratic ways we have to surface new leaders, right?

Sometimes someone doesn’t need to be well-connected or have a huge social media following. They just need a good idea and the courage to submit a talk about it, right? And that’s really powerful. And I think when someone gives their first talk and does well, they often become a mentor, a maintainer, a leader in that community, right? CFPs are literally how we build the next generation of contributors and speakers. So every talk is a potential origin story for someone’s open source journey.

Sally Cooper (07:08)

Puerco, what are your thoughts on that?

Sally Cooper (07:11)

And the question again is call for proposals can feel really intimidating, but they’re also one of the most important ways for new voices to enter a community.

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (07:20)

Yeah. So, I would say that intimidating is a very big word, especially for new people. maybe, Sometimes it’s difficult to ramp up the courage and I don’t want to mislead people into thinking it’s going to be easy. The first ones that you do, you will get up there, sweat, stutter, and basically your emotions will control your delivery and your body, so be prepared for that.

But it’s going to be fine. The next times you’ll do it, it will get better. And most importantly, people will not be judging you. In fact, it’s sometimes even more refreshing to see new voices getting up on stage.

Sally Cooper (08:13)

That’s really helpful. Thank you. I love it. The authenticity that you bring really helps and helps demystify the CFP process. But now let’s pull back the curtain on the review process. How does that work? And Stacey, have you been on a review panel before? Maybe you could talk about like, when you’re reviewing a CFP, what are you actually looking for?

Stacey (08:39)

Yeah, I’ve been on program committees. I’ve been on a program chair or co-chair on different programs and things like that. yeah, it’s a totally different experience, but I think it gives you lot of insight on how to prepare a talk once you’ve reviewed 75, 80 per session, right? It’s sometimes these calls are really big. I know KubeCon has really huge calls, right? But I would say, you know what we’re actually looking for:

So first, is this topic relevant and useful to our audience? Like, will people learn something they can actually apply? And second, like, can this person deliver on what they’re promising? And honestly, we’re looking we’re not looking for perfection, right? We’re looking for clarity and genuine expertise or experience like with that topic.

I would say be clear, be specific with your value proposition in the first two sentences of a CFP. When the program committee can read your abstract and immediately think, “oh that’s exactly what our attendees need,” right? That’s like gold, right? Also, when somebody shows that they understand the audience, that they’re they’re submitting to, right? Are you speaking to beginners or experienced practitioners and being explicit about that?

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (10:16)

Yeah, I think it’s important for applicants to understand who is going to be reviewing your papers. There are many kinds of conferences and I would… So ours, even though, of course, there’s commercial behind it because you have to sustain the event, like everybody involved in… Especially in the Linux Foundation conferences, I feel…

we put a lot of effort into making the conferences really community events. And I would like to distinguish the difference, like really make a clear cut between what is academic conferences, like purely trade show conferences and these community events. And especially in academia, there’s this hierarchical view of peers.

assessing what you’re doing. In pure trade show conferences, it’s mostly pay to play, I would say. And when you get down to community, especially if you ever applied to present or submit papers to the other kinds of conferences, you will be expecting completely different things. It’s easy to forget that people looking at your work, at your proposals, at your ideas is very, very close and very, very similar to you.

So don’t expect to be talking to some higher being that understands things much better than you. First of all, it’s not one person. It’s all of us reading your CFPs. keeping that in mind, what you need to keep like consider when submitting is what makes my proposal unique. I think that’s a key question. And we can talk more about that in the later topics, but I feel, to me, when I understood that it was sometimes even my friends reviewing my proposal made it so much easier.

Stacey (12:20)

Yeah, I think that’s a really, really good point Peurco makes is knowing that whatever conference you’re submitting for typically, and I say this like if it’s a Linux Foundation event, right? Because those are the ones that I’ve been most involved with. The program committee members are from within the community. They are, they submit an application to say, hey, yes, I would love to review talks. This is like me volunteering my time to help out this conference. Maybe they’re not able to make the conference.

Maybe they are, maybe they’re also submitting a talk. But usually the panel of reviewers is like five, six, up to 10 people, I would say, depending on the size of the conference. So you’re getting a wide range of perspectives reading through your submissions. And I think that’s really important. When I’m trying to select the program committee, I think it’s really important to diversify as well, right? So have voices from all over – different backgrounds, different expertise, different genders, just as much variance as you can have within the program committee panel, I think also makes a difference with the CFP reviews themselves, right?

But that’s kind of how it’s set up, is you pick these five to 10 people to review all of these CFPs, they have usually, it’s like a week or something like that to review everything, and then they rate it on a scale. And then that’s kind of how the program chairs then arrange the schedule is based off of all that feedback. You can make notes in each of the talks that you’re reviewing, you know, put those in there and then, and that’s basically how they’re all chosen. They’re ranked and they have notes, right, within that system.

Sally Cooper (14:08)

Wow, this is really educational. Thank you so much. For folks that are staring at a CFP right now, because there’s some coming up, and I think we’re going to get into that. Let’s get practical. What makes a strong abstract? How technical is too technical? How much storytelling belongs in a CFP? And what are some red flags that you might see in submissions?

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (14:34)

So, the first big no-no in community events is don’t pitch your product. Even if you trying to disguise it as a community event, the reviewers will … You have to keep in mind that reviewers have a lot of work in front of them. I am sure people, there are all sorts of reviewers, but usually as a reviewer, you see that folks put a lot of effort into crafting their proposals.

If you pitch your product, which is against the rules in most conferences, in the community conferences, the reviewer will instantly mark your proposal down. We can sniff it right away. You have to understand that for us, the more invalid proposals we can get out of the way as soon as possible, that will happen. If it is a product pitch, just don’t.

And then the next one is you have to be clear and concise in the first paragraph or sentence even. So when a reviewer reads your proposal, make sure that the first paragraph gives you an idea of, so this is going to be, I’ll talk about this and it’s gonna like…inspect the problem from this side or whatever, but give me that idea. And then you can develop the idea a little bit more on the next couple of paragraphs, but make sure that the idea of the talk is delivered right away. I have more, but I don’t know, Stacey, if you want to.

Stacey (16:20)

Yeah, no, I think that’s really good advice. would say whatever conference that you’re submitting, being on so many different program committees, I’ve seen the same talk submitted to every conference that has an Open CFP, regardless of the talk being specific to that conference or not. So think that’s key number one is make sure that what you’re submitting fits within the conference itself.

I think not doing a product pitch is key – especially within an open source community, open CFP, right? Those are only for open source, for non-product pitches. I think Puerco makes a really good point with that. But, you know, like, is this conference that I’m submitting this talk to higher level? Is it super technical and adjusting for those differences, right? A lot of times you’ll find in the CFPs that there is room to submit a beginner level, an intermediate level, an advanced level, but typically the conference description and the categories and things like this, you want to be very specific when you’re writing your CFP. You could sometimes you reuse the same CFP you’ve submitted to another conference, but you want to tailor it to each specific conference that you are submitting for.

Don’t just submit the same talk to five different conferences because they are unique, they are specific and you want to make sure that if you want your talk accepted, these are the little changes that make a big difference on really getting down to the brass tacks of what that conference is about and what they’re really looking for. So I always have to, when I’m writing something and when I’m looking at a conference to write it for, I have the CFP page up, I have the about page up for that conference and I’m making sure that it fits within what they’re asking me for, really.

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (18:20)

Yeah. And I just remember another one. And this is mostly, this happens most in the bigger ones, like the Cubicums and so on. Don’t try to slop your way into the conference. if you, I mean, it’s like, I’d rather see a proposal with bad English-ing or typos than something that was generated with AI. And I’ll tell you why.

It’s not because like, pure hates of AI or whatever. no. The problem with running your proposal into an LLM is that most of the time, so you have to keep in mind, especially in the big conferences, you will be submitting a proposal about the subject that probably then other people will be trying to talk about the same thing. And what will get you picked is your capability of expressing like…getting into the problem from a unique way, your personality, all of those things.

When you run the proposal through the LLM, it just erases them. All sorts of personal, like the uniqueness that you can give it will just be removed. And then it’ll be just like looking at the hollow doll of some of the person and you will not stand out.

Stacey (19:38)

Yeah, I agree completely – and…is it a terrible thing to have AI help you with some of the editing? No, not at all. But write your proposal first. Write it from your heart. Write it from your point of view. Write it from your angle. But do not create it in AI, in the chatbots. Create it from yourself first, and then ask for editing help. That’s fine.

I think a lot of us do that and a lot of people out there are using it for that extra pair of eyes. Do I sound crazy here? Does this make any sense? I don’t know how to word this one particular sentence. That’s fine. But yeah, don’t start that way.

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (20:19)

Exactly. mean, and just to make it super clear, it’s not that, especially people whose first language is not English like me. I of course use help of some of those things to like at least don’t like introduce many types or whatnot, but just as Stacey said, don’t create it there.

Sally Cooper (20:41)

This is great advice. Thank you both so much. Okay. How about getting accepted for a keynote? Like your KubeCon keynote really stood out. It was technical. It was really funny. memorable, engaging. How does someone prepare a keynote that differs from a regular talk?

Stacey (21:03)

Well, I want to start off by saying that we didn’t know, we weren’t submitting our talk for a keynote, right? We didn’t even know that that was like in the realm of possibility that could happen for KubeCon North America. We just submitted a talk that we thought would be fun, would be good, would give like, you know, some real world kind of vibes and that we wanted to have fun and we wanted to, you know, create a fun yet educational talk.

We had literally no idea that we could possibly have that talk accepted as a keynote. I didn’t know that. And this was my first real big talk. So it was a complete shock to me. I don’t know if you have other thoughts about that, but…

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (21:50)

Yeah, it sort of messes your plans because you had the talk planned for say 35 minutes and then you have 15 and you already had like 10 times more jokes that could fit into the 35 minutes. So, well…and then there’s also, course, like all of those things that we talked about, like getting nervous. Well, they not only come back, but they multiply in a huge way. I mean, you’ve been there. I don’t know. You get over it.

Stacey (22:28)

I would also say that once we found out that our talk was accepted first, were like, yay, our talk got accepted. And then I think it was like a few days later, they were like, no, no, your talk is now a keynote. So we freaked out, right? We had our little moment of panic. But then we just worked on it. And we worked on it, and we worked on it, and we worked on it, right? So not waiting till the last minute, I would say, to prep your talk.

But we…I think my main goal with this talk, and I have to give so much credit to Puerco because he’s such a good storyteller and he does it in such a humorous, but really technical and sound way. And we worked on this script. We wrote out an entire script because we only had 15 minutes. We went from a 25 minute talk to a 15 minute talk.

And so…pacing was really important, storytelling was really important, but also being funny was like something that I really wanted us to have, which Puerco was really good at too. And I think all of these things trying to squash it down into this 15 minutes was really tough, but I think that’s important to remember about keynotes versus talks is I think keynotes are more like, what is this experience of the talk about? Versus like, let’s get down to really technical details, right? You can do a technical talk that’s 25, 35, 45 minutes, but it’s a keynote. People aren’t going to remember anything from a keynote if you’re digging too, getting too deep in the weeds, right? So that was my focus. And I don’t know, Puerco, if you have anything else to add to that.

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (24:10)

Yeah, the other is that the audience is so much bigger that your responsibility just grows, especially to deliver, right? So as Stacey said, we actually wrote the script, rehearsed online, in person before the conference. And the experience also in the conference is very different because you have to show up early, you have to do a rehearsal in the prior days before your actual talk. And that’s said – nothing like it didn’t go perfect.

Like we still fumbled here and there and like messed up some of the details and the pacing and whatnot. it’s, I don’t know, at least in our case, it was about having fun and trying to get some of that fun into the attendees.

Sally Cooper (25:01)

Yeah, you really did. It was so fun. I think that’s what stood out.

Okay, one of the biggest barriers to submitting a CFP isn’t skill, it’s confidence. So what would you say to someone who feels like, I’m not expert enough. I don’t know if I have permission to do this. What you know, how do they deal? How do you personally deal with imposter syndrome? And why is it important to make sure that those new and diverse voices do submit at CFP?

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (25:27)

Oh, I’m an expert. So the first thing to remember, kids, is that Impostor Syndrome will never go away. In fact, you don’t want it to ever go away. Because Impostor Syndrome tells you something very, very important. And that is you are being critical of yourself, of your work, of your ideas. And if you ever stop doing that,

It means one, you don’t really understand the problem or the vastness of the problem that you’re trying to speak about and to talk about in your talk. And the other is you will stop looking for new and innovative ideas. So no matter where you get to, that imposter syndrome will ever be with you.

Stacey (26:20)

I agree. I don’t think it ever goes away. I feel like, you know, I was an imposter at the keynote. Absolutely was, right? Like, I didn’t know what the heck I was doing. I didn’t know what the heck I was saying half the time. I mean, I tried to memorize my lines and do the right thing and come off as this expert. I never, ever feel like an expert about anything, right? Unless I’m talking, I guess, about my cats or my kid or something.

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (26:47)

Yeah, exactly.

Stacey (26:49)

But yeah, think that’s, yeah, you’re pushing yourself to grow and that’s a good thing, right? So if you feel like an imposter, you know, that’s okay. And we all feel like that.

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (27:04)

Yeah. And the other, yeah, the other very important thing is think about what you are proposing to, to, to talk about in your talk. it’s supposed to be like new cutting edge stuff, like it’s something interesting, something unique. so it’s okay to feel about that because it’s, it’s a problem that you’re still researching that you’re trying to understand, that – especially think about – think about it this way.

If you propose any subject for your talk, anybody that goes there is more or less assuming that they want to know and learn more about it. if you feel confident enough to speak about it, like people will respond by willingness to attend your talk. That means you are already one little bit of a level above because you’ve done that research, you’ve done that in-depth dive into the subject. So it’s fine.

It’s fine to feel it. I realized that it’s a natural thing.

Stacey (28:05)

And most of the people in the audience are there to support you, to cheer you on, and are not gonna harp on you or say, oh gosh, you messed up this thing or that thing. They’re really there to give you kudos and really support you and be willing to hear and listen to what you have to say.

Sally Cooper (28:25)

Love that. Okay, let’s close the advice portion with a quick round of CFP tips rapid fire style. I’m going to go back and forth so each person can answer. Stacey will start with you. One thing every CFP should do.

Stacey (28:43)

I mean, get to the point as quickly as you possibly can. That would be my thing, right?

Sally Cooper (29:48)

Love it. Puerco, one thing people should stop doing in CFPs.

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (28:55)

Stop trying to blend or to mimic what you think the industry or your community wants from you. Represent. Always show off who you are, who you came from. That is super valuable and that’s why people will always want to have you as part of a program.

Sally Cooper (29:13)

Stacy, one piece of advice you wish you’d received earlier.

Stacey (29:18)

gosh, would say rejection is normal and not personal. I wish someone had told me that earlier, but that is one big, experience. Speakers get rejected all the time, right? It’s not about your worth. It’s about program balance, timing, and fit. So keep submitting.

Sally Cooper (29:39)

Okay, Puerco and Stacey, both got famous after this Puerco selfie or autograph?

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (29:44)

Selfie with a crazy face, at least get your tongue out or something.

Sally Cooper (29:50)

Stacey. KubeCon or KoobCon?

Stacey (29:54)

Oh gosh, I feel like this is like JIFF or GIF. And I’m in the GIF camp, by the way. I say KubeCon, even though I know it’s “Coo”-bernetes, I still say CubeCon, so.

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (30:07)

CubeCon, please.

Sally Cooper (30:09)

Okay, before we wrap up, Stacey, as the OpenSSF Community Manager, can you share some upcoming CFPs and speaking opportunities people should keep an eye on?

Stacey (30:19)

Yeah, so Open Source Summit North America is a pretty large event. I think it’s taking place in Minneapolis in May this year. There’s multiple tracks and there’s lots of opportunities for different types of talks. The CFP is currently open right now, but it does close February 9th. So go and check out the Linux Foundation Open Source Summit North America for that one.

We also have OpenSSF Community Days, which are co-located events at Open Source Summit North America, typically. And these are our events that we hold kind of around the world, but honestly, they’re perfect for first-time speakers as well. They’re smaller, they’re more intimate, and the community is super supportive. Our CFP for Community Day North America is February 15th. So go ahead and…search for that online. You can find them, and we’ll put the links in the description of this podcast so you can find that.

And then be on the lookout for key conferences later on in the year as well. KubeCon North America will be coming up later. Open Source Summit Europe is coming up later in the year. So be on the lookout for those. There’s also within the security space, I know there’s a lot of B-sides conferences and KCDs, which are Kubernetes community days and DevOps days.

If you’re in our OpenSSF Slack, we have a #cfp-nnounce channel that we try and promote and try and put out as many CFPs as we can to let people know that if you’re in our community and you want to submit talks regarding some of our projects or working groups or just OpenSSF in general, that CFP Announce channel is really a great place to keep checking.

Sally Cooper (32:13)

Amazing. Thank you both so much, not just for the insights, but for really making the CFP process feel more approachable and human. If you’re listening to this and you’ve been on the fence about submitting a CFP, let this be your sign. We really need your voice and thank you both so much.

Stacey (33:32)

Thank you.

Adolfo García Veytia (@puerco) (33:33)

Thank you.

Planning to attend KubeCon + Cloud Native Con Europe in March? Don’t miss OpenSSF’s co-located 1-day event! This gathering will bring together a diverse community, including software developers, security engineers, public sector experts, CISOs, CIOs, and tech pioneers, to explore challenges and opportunities in modern security. Collaborate with peers and discover the essential tools, knowledge, and strategies needed to ensure a safer, more secure future.

Planning to attend KubeCon + Cloud Native Con Europe in March? Don’t miss OpenSSF’s co-located 1-day event! This gathering will bring together a diverse community, including software developers, security engineers, public sector experts, CISOs, CIOs, and tech pioneers, to explore challenges and opportunities in modern security. Collaborate with peers and discover the essential tools, knowledge, and strategies needed to ensure a safer, more secure future. Join us for the first OpenSSF Tech Talk of the year, focusing on agentic artificial intelligence (AI) security.

Join us for the first OpenSSF Tech Talk of the year, focusing on agentic artificial intelligence (AI) security. OpenSSF has released a new Compiler Annotations Guide for C and C++ to help developers improve memory safety, diagnostics, and overall software security by using compiler-supported annotations. The guide explains how annotations in GCC and Clang/LLVM can make code intent explicit, strengthen static analysis, reduce false positives, and enable more effective compile-time and run-time protections. As memory-safety issues continue to drive a significant share of vulnerabilities in C and C++ systems, the guide offers practical, real-world guidance for applying low-friction hardening techniques that improve security without requiring large-scale rewrites of existing codebases.

OpenSSF has released a new Compiler Annotations Guide for C and C++ to help developers improve memory safety, diagnostics, and overall software security by using compiler-supported annotations. The guide explains how annotations in GCC and Clang/LLVM can make code intent explicit, strengthen static analysis, reduce false positives, and enable more effective compile-time and run-time protections. As memory-safety issues continue to drive a significant share of vulnerabilities in C and C++ systems, the guide offers practical, real-world guidance for applying low-friction hardening techniques that improve security without requiring large-scale rewrites of existing codebases.  Security Slam 2026 is a 30-day security hygiene challenge running from February 20 to March 20, culminating in an awards ceremony at KubeCon + CloudNativeCon Europe. Hosted by OpenSSF in partnership with CNCF TAG Security & Compliance and Sonatype, the event encourages projects to use practical security tools, including OpenSSF resources, to strengthen their security posture based on their maturity level. Participants can earn recognition, badges, and plaques for completing milestones, reinforcing a community-driven effort to improve open source software security at scale.

Security Slam 2026 is a 30-day security hygiene challenge running from February 20 to March 20, culminating in an awards ceremony at KubeCon + CloudNativeCon Europe. Hosted by OpenSSF in partnership with CNCF TAG Security & Compliance and Sonatype, the event encourages projects to use practical security tools, including OpenSSF resources, to strengthen their security posture based on their maturity level. Participants can earn recognition, badges, and plaques for completing milestones, reinforcing a community-driven effort to improve open source software security at scale.  At FOSDEM 2026, the CRA in Practice DevRoom brought together open source and industry leaders to turn the EU Cyber Resilience Act from policy discussion into practical action. Through case studies and panels, speakers shared concrete approaches to vulnerability management, SBOMs, VEX, risk assessment, and the steward role.

At FOSDEM 2026, the CRA in Practice DevRoom brought together open source and industry leaders to turn the EU Cyber Resilience Act from policy discussion into practical action. Through case studies and panels, speakers shared concrete approaches to vulnerability management, SBOMs, VEX, risk assessment, and the steward role.  On February 2, OpenSSF convened the Package Manager Security Forum, bringing together maintainers and registry operators from major ecosystems to address shared challenges in package repository security. Discussions highlighted common concerns around identity and account security, governance and abuse handling, transparency, and long-term sustainability. The session reinforced that package ecosystem risks are interconnected and that improving security requires cross-ecosystem coordination, shared frameworks, and continued collaboration through OpenSSF’s neutral convening role.

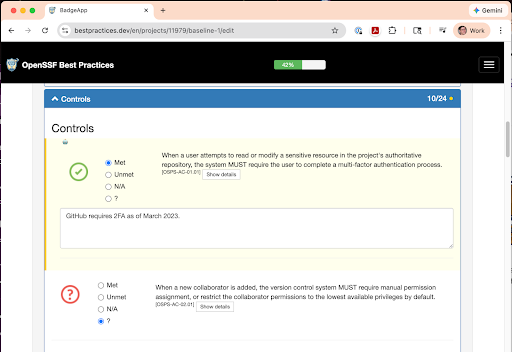

On February 2, OpenSSF convened the Package Manager Security Forum, bringing together maintainers and registry operators from major ecosystems to address shared challenges in package repository security. Discussions highlighted common concerns around identity and account security, governance and abuse handling, transparency, and long-term sustainability. The session reinforced that package ecosystem risks are interconnected and that improving security requires cross-ecosystem coordination, shared frameworks, and continued collaboration through OpenSSF’s neutral convening role. Is your open source project meeting the “minimum definition” of security? The OpenSSF has officially integrated the Open Source Project Security Baseline (OSPS Baseline) into its Best Practices Badge Program.

Is your open source project meeting the “minimum definition” of security? The OpenSSF has officially integrated the Open Source Project Security Baseline (OSPS Baseline) into its Best Practices Badge Program.

Understanding and Completing the Baseline Criteria

Understanding and Completing the Baseline Criteria Dr. David A. Wheeler is an expert on developing secure software and on open source software. He created the Open Source Security Foundation (OpenSSF) courses “Developing Secure Software” (LFD121) and “Understanding the EU Cyber Resilience Act (CRA)” (LFEL1001), and is completing creation of the OpenSSF course “Secure AI/ML-Driven Software Development” (LFEL1012). His other contributions include “Fully Countering Trusting Trust through Diverse Double-Compiling (DDC)”. He is the Director of Open Source Supply Chain Security at the Linux Foundation and teaches a graduate course in developing secure software at George Mason University (GMU).

Dr. David A. Wheeler is an expert on developing secure software and on open source software. He created the Open Source Security Foundation (OpenSSF) courses “Developing Secure Software” (LFD121) and “Understanding the EU Cyber Resilience Act (CRA)” (LFEL1001), and is completing creation of the OpenSSF course “Secure AI/ML-Driven Software Development” (LFEL1012). His other contributions include “Fully Countering Trusting Trust through Diverse Double-Compiling (DDC)”. He is the Director of Open Source Supply Chain Security at the Linux Foundation and teaches a graduate course in developing secure software at George Mason University (GMU).

As cybersecurity legislation such as the

As cybersecurity legislation such as the  Curious about what security topics will shape the open source world in 2026 and how you can be part of it?

Curious about what security topics will shape the open source world in 2026 and how you can be part of it?  What does good security actually look like for open source projects? This new blog walks through the community-developed OSPS Baseline, a catalog of practical security controls that helps projects understand expectations, improve over time, and meet users where they are. With FOSS in up to 96% of modern codebases and relied on across nearly every industry, the blog explains why shared security practices matter and how the Baseline connects to standards like NIST SSDF, the EU Cyber Resilience Act, and ISO 27001. It also links to keynotes, a tech talk, a podcast, a real project case study, and FAQs so you can see how the Baseline works in practice.

What does good security actually look like for open source projects? This new blog walks through the community-developed OSPS Baseline, a catalog of practical security controls that helps projects understand expectations, improve over time, and meet users where they are. With FOSS in up to 96% of modern codebases and relied on across nearly every industry, the blog explains why shared security practices matter and how the Baseline connects to standards like NIST SSDF, the EU Cyber Resilience Act, and ISO 27001. It also links to keynotes, a tech talk, a podcast, a real project case study, and FAQs so you can see how the Baseline works in practice.  OSSAfrica is a new community-led initiative working to strengthen open source security across Africa by connecting contributors, maintainers, developers, and security practitioners. Operating as a Special Interest Group under the OpenSSF BEAR Working Group, OSSAfrica focuses on community building, security awareness, locally relevant solutions, and creating clear pathways for African contributors to engage in global open source security efforts. Learn why this work matters, what’s being built, and how you can get involved.

OSSAfrica is a new community-led initiative working to strengthen open source security across Africa by connecting contributors, maintainers, developers, and security practitioners. Operating as a Special Interest Group under the OpenSSF BEAR Working Group, OSSAfrica focuses on community building, security awareness, locally relevant solutions, and creating clear pathways for African contributors to engage in global open source security efforts. Learn why this work matters, what’s being built, and how you can get involved.